Addressing society’s evolving needs requires tackling interconnected issues – climate change, resource depletion, pollution, and biodiversity loss – simultaneously. The built environment’s longevity and interdependence demand strategic, long-term, and integrated governance. Yet siloed structures in government, regulation, and industry, along with fragmented data, hinder progress and obscure the insights needed to improve outcomes. Without urgent action, we risk cascading system failures, economic harm, and widespread hardship. To create better outcomes where people and nature thrive, planners must understand the system of systems we rely on. A systems thinking mindset is essential for better governance and more effective interventions. At the heart of this approach is co-creating shared understanding to build consensus and foster a connected community for change. This enables shared language, aligns goals, and supports cross-sector collaboration. The paper presents core principles to advance systems thinking and drive positive change in the built environment. It is an approach with international relevance for change-makers in the built environment.

Keywords: Systems Thinking; Built Environment; Infrastructure; Outcomes; Interventions; Change

Mark is a keen champion of outcomes-focused systems thinking, collaborative delivery models, digitalisation, connected digital twins and the circular economy in the built environment. Mark is the Royal Academy of Engineering Visiting Professor in the digitalisation of the built environment at the University of Cambridge, and he is a Visiting Professor in the De ...

The Built Environment is a Complex System of Systems

Our built environment consists of interdependent systems that provide essential services for society. It includes our economic, social and urban infrastructure, together with their interfaces with our natural environment. The built environment is the host for all the other essential systems that operate within it, such as the financial, health, education and justice systems. And it faces complex challenges.

Co-Creating a Shared Understanding and an Agenda for Change

Central to the approach is co-creating a shared understanding to build a consensus and grow a connected community to drive change.

A shared understanding is a prerequisite for connected change. It is needed to:

This paper describes the approach and presents key aspects of the emerging shared understanding.

We Face Interconnected Challenges That Cannot Be Solved in Isolation

Climate change, resource limitation and biodiversity loss are interconnected challenges that demand a systemic approach. Our current approach, characterized by siloed decision-making and focused on individual new projects, is inadequate. Without addressing connected issues in a connected way, we are at best missing opportunities, and at worst headed towards multiple systems failures, economic damage and widespread hardship. Without systems thinking, which helps us to grasp interconnectivity and deal with complexity, we expose ourselves to risks that could compromise our security – energy, food, health and even national security. The cost of inaction is too high.

The Way We Manage the Built Environment Is Not Set Up to Meet These Challenges

The organizations that regulate and operate the built environment are not well connected. Sector silos run from government departments, through regulators to owner/operators. There is no body that provides a joined-up view of the existing built environment or how new developments impact the outcomes of the overall system.

We fail to realize the value of the existing built environment because we make siloed decisions that do not take account of its interconnected nature. Building new is prioritized over better management of

what we have already built. This reduces asset lifespans, increases whole life costs and impairs service delivery. Siloed and short-term planning produces unpredictable fluctuations in investment, reduced resilience and greater environmental impact.

We miss opportunities to gain more value from our existing assets due to inadequate data management, limited interoperability and insufficient information flow across organisation or sector boundaries. The information required to run the built environment is poorly connected.

Our fragmented approach results in wasted resources, missed opportunities and unintended consequences. It hinders our ability to achieve a sustainable, resilient and equitable future. It is time to shift from heroic individualism to collective endeavor.

Positive Systems Change Is An Urgent Necessity

It will become impossible to meet society’s evolving needs unless we address the connected challenges we face. In this context, it becomes evident that we need a more connected approach to managing the built environment. Specifically, we need an approach that is outcomes-focused, systems-based and community enabled. Further, in order to achieve this, it is necessary both to advance systems thinking in the built environment and to drive positive systems change.

A Methodology To Enact Change

In contrast to traditional methods of data collection and analysis, our methodology was focused on enacting change as an iterative learning journey. From the beginning, our methodology had the clear intent of using the co-creation process as a means of growing a community with the consensus to drive positive systems change. The methodology was an inclusive, and emergent process that prioritized community engagement and consensus building.

The process was designed around listening, recording, reflecting, pattern spotting, and iterating. It specifically allowed for and expected emergence, meaning it did not start with a premeditated solution. Instead, it allowed patterns of answers to appear, which were then fed back to and tested with the growing community. This iterative approach ensured that the solutions were not only relevant but also collectively owned by the community.

Listening and Recording

The learning journey was initiated through a series of interviews and workshops with a diverse group of stakeholders, including representatives from government, industry, academia and civil society. This early engagement generated a wide range of views, which were carefully considered, recorded and sorted into ‘key points’ that were each given a number and a title so that they could be identified and commented on individually. When someone raised a key point that had been made before, it was not recorded separately. Instead, the original record was modified to capture any new perspective. By the end of the process, we had identified around one hundred separate key points.

Reflecting and Pattern Spotting

Even from the earliest interviews and workshops, when there were a limited number of key points, reflection revealed patterns and connections. It became clear from early on that a basic ‘why/what/how’ structure helped to make sense of the key points. As the number of key points increased, it became necessary to add ‘who/where/when’ to the structure. Further reflection enabled us to begin to arrange the key points with a narrative flow within the structure. This became our ‘source material’ document.

From that starting point, we could build a holistic understanding of the challenge. This challenge was bounded on one side by the existing conditions before our engagement and on the other side by a shared vision for the built environment: enabling people and nature to flourish together for generations [1].

Iterating

Stakeholder reviews played a crucial role in our iterative co-creation process. Each version of the ‘source material’ document was shared with stakeholders, and feedback was integrated into the document, ensuring that all viewpoints were considered. Then we held more workshops, identified more key points, integrated them into the document and shared it with more stakeholders. By the end of the process, we had engaged with over two hundred stakeholders.

As iterative updates were made based on the feedback received, the document underwent multiple versions, each incorporating new insights and comments, ensuring that it evolved through collective input from a growing group of stakeholders. In this way, we not only developed the document, but also grew the community.

Output Development and Action-Oriented Focus

The source material document was key output from the co-creation process. It includes practical recommendations for immediate steps to drive positive systems change, particularly within the UK context. This action-oriented focus ensures that the shared understanding is not only theoretical but also practical and implementable.

The source material document is a valuable resource in itself. However, at 16,000 words, it is too long for many people to read, therefore it best serves as a reference that can be used for generating other outputs that can be tailored to specific audiences.

The first additional output that has been generated in this way is a white paper called Connect to change [2]. Focused on change-makers, this paper serves as a succinct summary, presented in plain English in order to be highly accessible.

Overall Benefits of the Approach

The results demonstrate the benefits of an interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral, multifunctional, multiscale, multidomain, and multistakeholder approach. First, the approach shows that a cross-sectoral shared understanding can be co-created with public, private and third sector participation. Second, it shows that the co-creation process can be used to grow a community with a consensus to drive positive systems change.

Beyond that, the emerging shared understanding demonstrates a growing consensus that a systems thinking mindset is essential to improve governance and to intervene more efficiently and effectively in the built environment. There is agreement that applying systems approaches in the built environment has the potential to create a more sustainable, resilient and equitable future.

Therefore, it is time that we saw the built environment differently – not as a series of construction projects, but as a system of systems with the explicit purpose of delivering the services that will enable people and nature to flourish together for generations.

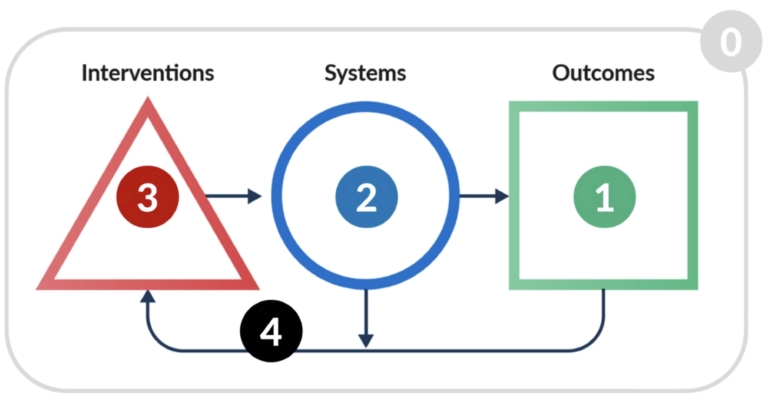

A Shared Theory of Change

Fundamentally, to improve outcomes for people and nature, we must understand our built and natural systems better, so that we can deliver more effective interventions. This connection between outcomes, systems, and interventions is central to improving the built environment as a complex system of systems – and it reflects a common theory of change.

Using this framework, systems approaches can be applied at any level – from cities to infrastructure interfaces or supply chains. Though challenges are complex, the process can be broken into clear, repeatable steps:

The Key To Driving Positive Systems Change

Many relevant communities already exist that are eager to drive positive systems change in the built environment. Given the diversity and autonomy of these stakeholders, the overall approach must be to convene, connect, and coordinate aligned communities, rather than run a traditional top-down change program.

The key is to connect communities of action with a consensus to drive change:

This paper underscores the urgent need for a systems thinking approach to address the interconnected challenges within the built environment. The current fragmented and siloed management practices are inadequate for tackling issues such as climate change, resource depletion, and biodiversity loss. By co-creating a shared understanding among diverse stakeholders, we can foster meaningful communication, align efforts towards common goals, and drive positive systems change.

The methodology presented, which emphasizes iterative learning and community engagement, has proven effective in building a consensus and growing a connected community. This approach not only enhances governance but also enables more efficient and effective interventions. The core principles outlined provide a practical framework for advancing systems thinking in the built environment.

Ultimately, the paper highlights the importance of collective effort and a shared vision to create a sustainable, resilient, and equitable future. By adopting a systems thinking mindset, we can better understand and manage the complex interdependencies within the built environment, ensuring that people and nature can flourish together for generations to come.

[1] Our Vision for the built environment: https://www.visionforbuiltenvironment.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Vision_090621.pdf

[2] Connect to change: https://be-connective.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Connect-to-change.pdf