Good hand-offs from one performer to the next have always been an important part of the Last Planner System® (LPS). LPS features a rigorous process for making reliable commitments and the Percent Plan Complete (PPC) metric to measure how many were done as promised. LPS and PPC have helped reduce waste and frustration in countless weekly planning meetings and represent a major step forward in how we think about work on projects. Reliable commitments and PPC, however, focus primarily on the upstream side of the hand-off: What are we committing to do? What about commitments on the other side of the handoff: Who is committing use what was produced and how quickly will they do so?

This paper explores taking a closer look on the receiving side of the hand-off and suggests an additional metric, Mutual PPC, to find those tasks for which there is both a commitment to perform the task and a corresponding commitment to take advantage of that completion without delay. At least in the author’s experience, the number of tasks meeting both criteria is smaller than you might expect. Adding an extra bit of conversation to the planning process can pay big dividends and give teams a better chance of realizing the full potential of LPS, including the reduction of unnecessary Work-in-Process (WIP) which will naturally help shorten cycle times.

This paper is based on observations that pure Pull and continuous Flow are quite rare on projects and will provide some insights into how to effectively make steady progress towards schedule Milestones while simultaneously enabling production crews to create a smooth and predictable flow of work. The concept of Last Responsible Moment, an essential part of the conversation, will also be described in a fresh way.

Keywords: PPC; Critical PPC; Flow; Futile Hurry; Phantom Demand; Last Planner System®; Last Responsible Moment; Last Feasible Moment; Concentrated Effort; Critical Chain; Workable backlog; Earned Value

John Strickland has been a pioneer in bringing innovative thinking to the Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) industry with passion for workplace safety, learning, innovation and smooth flow. Many years of jobsite and corporate construction operations leadership combined with extensive study and research of project delivery systems led t ...

A relay race offers one illustration of poor flow on projects. At high levels of competition, relay races are won or lost in the exchange zones. The objective is to keep the baton moving and nobody would consider a strategy in which batons were left in piles at random spots along the course. Even more absurd would be a relay race in which it wasn’t clear which specific runner would next carry the baton or how they would know which baton to select from a pile left by previous runners. That dysfunctional relay race provides an apt metaphor for some large projects prior to the introduction of LPS.

Pure “Pull” is quite rare on projects. Think about it - Do we complete work for which there is not a clear downstream customer? Is equipment or material rushed to the jobsite only to sit unused for an extended period and then moved multiple times to get it out of the way? How often have crews had their work disrupted in response to complete some emergency only to see their efforts wasted as “futile hurry?” How often do we put in extra effort and sacrifice to complete a task only to subsequently learn that our work was not immediately used, and maybe not used at all. Do downstream customers sometimes ask for far more of something than they need or ask for it far sooner than they need it to build buffer for themselves – something we could call “phantom demand?” There’s good reason to believe these things still happen. In each of those cases a well designed project production system and a sharper focus on hand-offs during planning meetings might eliminate a lot of wasted effort and frustration.

The key flows covered in this paper are the smooth flow of tasks towards reaching Milestones (Work Flow) and the smooth flow of work for the various work crews (Crew Flow, also known as Trade Flow). There are countless flow streams within projects, and, with very few exceptions, work completed at one step creates a stockpile of work for some subsequent step. For nearly all work streams:

There will either be work waiting for workers or workers waiting for work.

Attempting to keep all work streams moving and all workers working is futile and creates great frustration for the participants. The Weekly Planning Meeting is a key forum to find the balance between making sure that critical work isn’t waiting for workers and that workers aren’t frustrated by unpredictable or unreasonable work schedules. A well-designed and managed production system is invaluable, but the final critical step involves the conversations at the weekly planning meeting. These conversations can help you decide how much work buffer you need, who needs it, and when completing tasks just creates unhelpful Work In Process (WIP).

Crew Flow represents the difference between success and failure for contractors and looks different in their eyes than in the eyes of the Owner or Construction Manager. The crews working on a particular job may not be dedicated to it. The supporting fab shops are almost certainly balancing one project’s demands with those of many others. I have found it best to initiate transparent conversations and, to the degree possible, support the business goals of the contractors to create Crew Flow.

Identifying the tasks that really matter, and providing some slack on the others creates flexibility, enhances teamwork and has worked out much better for me than relying on contractual leverage in an effort to optimize Work Flow without regard to Crew Flow. This doesn’t mean we sacrifice schedule performance to make it easy for contractors to make money. We will see that optimizing Trade Flow is not at the expense of the Work Flow that matters.

The founders of LCI, which included Todd Zabelle, founder of the Project Production Institute, recognized the importance of creating Flow and managing WIP, which are the keys to reducing Waste. Early adopters quickly learned to focus on the key hand-offs between performers and their relay races started producing better results. They embraced thinking that seems radical –even crazy, maybe – to those not indoctrinated with Lean thinking:

Perform work only when requested (pulled) from the downstream customer.

In other words, avoid performing any work unless somebody asks for it and is ready to use it . Strategic Project Solutions introduced a new term, Last Responsible Moment (LRM) to help us visualize working at the Pull of the downstream customer (or performer) and clarifying the last moment that the work can be released without disrupting downstream work.

This is in stark contrast to conventional management thinking, in which we try to do as much as we can as soon as we can. There is, however, a critical caveat often misunderstood that often lead those new to Lean thinking to dismiss the key ideas altogether:

LPS in no way advocates letting everything slip to the last possible moment – that would be irresponsible.

The key word is “responsible” and includes appropriate buffers and allowances and not adding unnecessary risk. A trip to the airport provides an example. In normal traffic times I’ve found that I can leave my home 2.5 hours before flight time and have a comfortable, but not excessive, buffer to deal with problems or enjoy a pre-flight snack. That duration determines the LRM. I might, however, leave only 90 minutes ahead of flight time and still catch the plane if I were willing to ignore speed limits, find light traffic and park in the expensive short-term lot. I would consider that approach irresponsible, but the 90-minute duration would define the “Last Feasible Moment” (LFM). Understanding both LRM and LFM is important if for no other reason than to constantly remind participants that LRM and LFM are not the same thing.

Over the years, I’ve noted many times that tasks were completed later than the expected LRM yet we still met the schedule. Similar to the way in which only a few Critical PPC tasks control progress towards the Milestone it seems we can frequently find ways to accommodate some tasks going past LRM., The key word is “some:” Tasks that go beyond the LRM add risk to the project that grows exponentially as their numbers increase. We might deal with a few such tasks but will fail if confronted by too many. Acknowledging the number of “LFM” Tasks – those not expected to meet LRM – might be a very useful practice.

It turns out that a small percentage of project tasks for the upcoming week will control Work Flow – the flow of work towards meeting the next Milestone. So, how do we find them? It’s simpler than you might think:

Which activities can reliably be promised for the upcoming work period which will immediately be worked upon by the next performer rather than placed in a queue? Look for not only a promise to do the work, but a corresponding promise to use it as part of the conversation for commitment.

That’s where you will find the Work Flow that matters the most. Similarly, which crews already have large queues of work in front of them, such that an upstream crew completing tasks will simply add WIP?

Several years ago, I began experimenting with an addition of a new concept and metric, Mutual PPC (originally labeled “Critical PPC”). Early implantations confirmed observations that LPS participants routinely committed to hand-offs for which there was no clear immediate customer unless specifically and repeatedly coached otherwise. Some were also prone to commit to more tasks than they could reasonably complete. The drive to “push” work is deeply ingrained. It became clear that, at least in the sessions I was observing, that some promises were much more important than others and that we could greatly reduce our stress if we identified which ones they were. So, we added a simple step to our planning conversations. This observation was confirmed on multiple projects including one nearing a First Product Milestone, in which we found that even in the last few weeks , more tasks than not went into queues.

This insight has helped projects avoid lots of pointless overtime work and reduce peak headcount levels. Countless times I’ve asked crews planning to work overtime hours to identify who would immediately take advantage of their extra effort and found there was no clear answer. Why, then, would we pay extra to have the work done earlier than can be utilized? Similarly, we can help our trade partners avoid bringing on more staff than otherwise needed to meet the Mutual PPC requirements and then find they have “run themselves out of work” and release the workers that wouldn’t have needed to be hired, trained and outfitted. This thinking has allowed projects to significantly lower peak manpower while simultaneously pulling in the schedule.

This thinking can have big financial implications. In the early days of Lean Construction, I was preparing a strategy to apply LPS to a large-scale project to install semi-conductor manufacturing equipment – possibly the world’s largest such facility at the time and one of the largest LPS implementations. I engaged Todd Zabelle, Glenn Ballard, James Choo and others at Strategic Project Solutions (SPS) to help my team design and implement a robust work planning system. The concept of Making and Keeping Reliable Promises promoted by Greg Howell and Hal Macomber, was also new at the time and introduced during the early stages of the project. We managed specifically for both Work Flow (important to the Owner) and Crew Flow (important to the Contractors) and worked to create a culture of respect and reliable commitments. The project turned out to be successful beyond anybody’s expectation. Our customer project managers still rate that project among the best of their careers as the factory start-up date was pulled in by more than 2 months (on an 18 month ramp) while simultaneously reducing peak headcount by 24%. If you visualize the manpower curve, both the length and height of the curve were sharply reduced. Safety metrics were world-class. High quality results were easier because more of the work was done by the best crews, and we avoided the short-term peak headcount spikes. We didn’t rely on overtime to pull in the schedule as those hours represented only 2% of the work hours through the busiest part of the schedule. We (as the construction integration firm) made great money, the trade contractors made even more and the client made lots and lots of money. In sharp contrast to most large tool installation projects of that era, the typical day was uneventful with less stress, drama and staff turnover than previously experienced. I sometimes refer to the project as “construction in Mayberry” in reference to the idyllic setting of the Andy Griffith TV series. That experience sealed my destiny – I could no longer imagine a return to a confrontational and transactional project delivery approach.

There are, of course, many valid reasons for completing work earlier than the Pull schedule would indicate, such as making a crew available for some other task or taking advantage of favorable work conditions. These valid reasons are revealed and respected during the brief conversation.

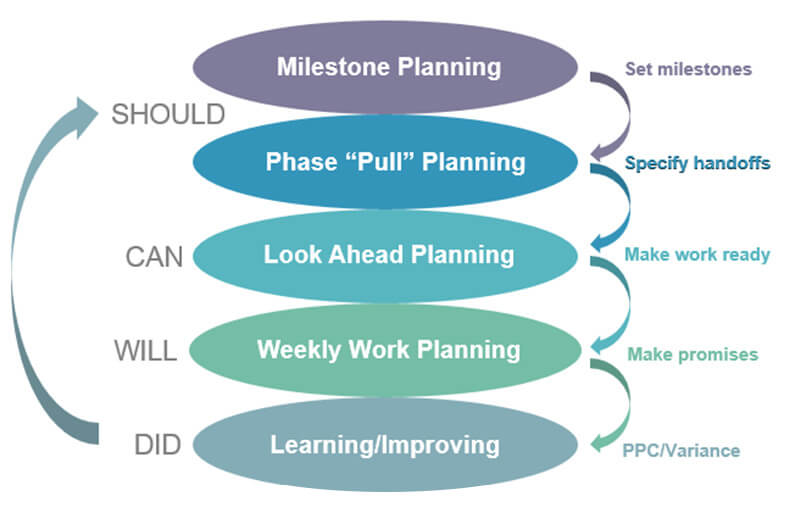

Applying the Mutual PPC concept is a relatively small update to the familiar LPS system diagrammed below:

Mutual PPC simply adds a “will use” commitment to the “will do” commitment already shown. This not only helps identify the most important hand-offs but also discourages “Phantom Demand” – the tendency for the downstream customer to demand more work or earlier completion than really required.

We also recognized that monitoring how much work was represented in the various stages of readiness was a convenient way to promote flow through the system. In general, we encouraged our Last Planners to commit no more than about 70% of their crew’s capacity to “Will Do” tasks but also make sure there was ample “Can Do” work, perhaps 50% of capacity” to make sure the crew didn’t run themselves out of work. Those were early general guidelines. As work becomes more predictable the amount of capacity that can be promised will increase. A more advanced application of Operations Science will help us better define the appropriate buffers.

Readers may note there is no category for Workable Backlog. They might find that omission odd considering how important that buffer can be. Workable Backlog is still important and it’s still there. All of the Work that meets the requirements for “Ready” but which is not yet “Committed” or “Critical” aligns with the definition of Workable Backlog that has been in place for many years.

The Mutual PPC concept also helps us deal with an awkward problem in our planning process – Uncertainty of task durations. Goldratt and others have explained this problem well and it is not hard to find hedging and buffers built into estimates of completion dates. As Goldratt noted in Critical Chain, the over-all duration for a string of tasks can have more buffer than value-added work. This seems similar to what my colleagues and I have observed many times when mapping production processes – and a key finding from Operations Science – that work spends most of the overall duration in Queues.

Concentrated Effort for each task, which is how long the task would take if it were completed without interruption and without sharing resources with other tasks, should be addressed. Of course, that is how we hope the task will be performed, but experience suggest that is not common across the industry. Note that crew leaders will often be reluctant to reveal the Concentrated Effort unless they are working in a high-trust environment. It may take some time before you are able to eliminate the Buffer embedded into most durations.

Sometimes crew leaders just don’t know, and cannot know, how long it will take to complete a task. A natural response to the pressure for a Reliable Commitment might be simply adding buffer time. For non-Mutual PPC tasks we might not need to challenge the duration. For Mutual PPC tasks, we can acknowledge reasonable uncertainty regarding how long the task will take and allow a range of durations because we want the downstream performer to be able to take advantage of the earlier duration. Think back to our relay race: The downstream runner must be able to adapt to the speed and timing of the runner carrying the baton. That means that the downstream performer will potentially have some excess capacity waiting for the baton. On construction sites we can provide crew with adequate Released, but not Committed work (aka Workable Backlog) to remain relatively well utilized that can be interrupted to allow them to respond to the possible variation in the Critical task.

Willie Sutton, a bank robber, was famously asked “Why do you rob banks”? He is said to have responded “Because that’s where the money is.” Similarly, this paper advocates focusing on those tasks for which the performer can make a reliable commitment to complete a task and the next performer commits to take advantage of the completion without delay. That’s where the Flow is. That’s how you find the baton exchanges that matter most and help teams avoid losing site of the benefits of pull based scheduling.

Many of the concepts presented in this paper have long been understood by the founders of the Lean Construction Institute and Project Production Institute and the author is much in their debt for the insights they have provided over the years. Advanced users of Operations Science and Takt Planning have likely already addressed many of the issues described. Nothing in this paper is intended to discount LPS, including the numerous updates proposed by Glenn Ballard and Iris Tommelein.

Many people have contributed to my understanding of key concepts with special thanks to:

Greg Howell, Glenn Ballard, Iris Tommelein and Todd Zabelle – the sparks that ignited Lean Construction

James Choo and colleagues at Strategic Project Solutions

Jeff Loeb and the Lean Project Delivery team at CH2M (now Jacobs).

Hal Macomber

Iris Tommelein

Alan Mossman

Sean Graystone

Fernando Espana Dan Fauchier