Getting projects off to a good start is the aspiration of every project manager and a critical first step towards smooth flowing work later. Unfortunately, many of our large projects are stymied before the construction team gets a chance to mobilize. Few aspects of project delivery are more disruptive or wasteful than discovering the desired scope cannot be completed at an acceptable cost after most of the design budget has been spent and bidders have been thoroughly exercised. Project after project suffers through this frustration yet the industry continues to utilize the same basic process, analogous to holding a position on the beach while being soaked by wave after wave. Maybe we don’t move because we fail to recognize just how big the waves have become, how much waste is really involved or that there are very practical alternatives. Projects would be much more successful and provide a much better experience for the participants if we could eliminate this Big Waste.

Some of the waste is readily apparent. The wasted effort of preparing detailed design documents that are subsequently reworked or discarded and the effort wasted by bidders is not difficult to visualize. he time lost to value engineering, re-design and re-bidding leads to either expensive schedule compression or delayed benefit and is also quite evident. A still larger, but less commonly recognized, waste could be the opportunity cost of features and value unnecessarily stripped out of the project or never considered during the design process.

The struggles are not over even after initial agreement has been reached and contracts are signed; most project teams seriously over-estimate the degree to which they understand the project Scope and how it will be accomplished [1]. In other words, the conventional process will likely conceal misalignment and cause even greater disruptions when it is finally discovered. As with any quality problem, the sooner we can address the underlying misalignment the better we will be able to mitigate it.

Part of the issue described above deals with timing, communication and commercial tactics. This challenge is addressed by many other papers and will be described briefly in this one. The typical Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) is also part of the problem because typically does not extend to become a Work Integration System. This paper will describe the Collaborative Design and Scoping (CDS) can be combined with Fundamental Scope Blocks (FSBs) to help us address one of the underlying root causes of lousy system performance.

The benefits of the CDS and FSB concepts create value beyond launching the project. Creating the basic units of work that will subsequently flow through the project production system is equally important. Organizing the work into chunks aligned with how it will be performed, coupled with an understanding of how chunks affect one another creates a great foundation for creating flow. The combination of the smoother start and smoother downstream flow will make your projects more successful, less risky, and much more rewarding for the participants.

Keywords: Collaborative Design and Scoping (CDS), Fundamental Scope Blocks (FSBs), Work

Integration System, Lean Construction, Advanced Work Packaging

John Strickland has been a pioneer in bringing innovative thinking to the Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) industry with passion for workplace safety, learning, innovation and smooth flow. Many years of jobsite and corporate construction operations leadership combined with extensive study and research of project delivery systems led t ...

Wouldn’t it be great if the entire design budget and duration were not exhausted until we were confident the project was technically feasible and could be completed at an acceptable cost? Those are the key ideas behind Target Value Delivery and Project Validation frequently promoted by the Lean Construction Institute (LCI), but these techniques are not a complete answer. What if TVD and Project Validation could be done rapidly with features linked clearly to costs in a concise and easily scannable format? That would greatly improve the Owner’s ability to make key decisions and trade- offs. Going further, imagine that the process for defining Scope enabled smooth flow throughout the rest of the project. This would reduce waste and frustration for nearly everybody. Finally, imagine that enormous amounts of design and pre-construction production capacity that could be re-allocated to high-value activities? Maybe resource availability wouldn’t be such an issue if we weren’t wasting it on poorly aligned communication processes.

The ideas presented in this paper have been brewing for more than 25 years and successfully tested on many projects. Many Lean Construction pioneers and thought leaders have participated in developing the concepts and techniques, yet we still see familiar problems It seems we are well anchored to our spot on the beach and take comfort in a delivery process that is familiar, if not effective. Maybe looking at old problems in a new way will lead us to seek a path to higher ground.

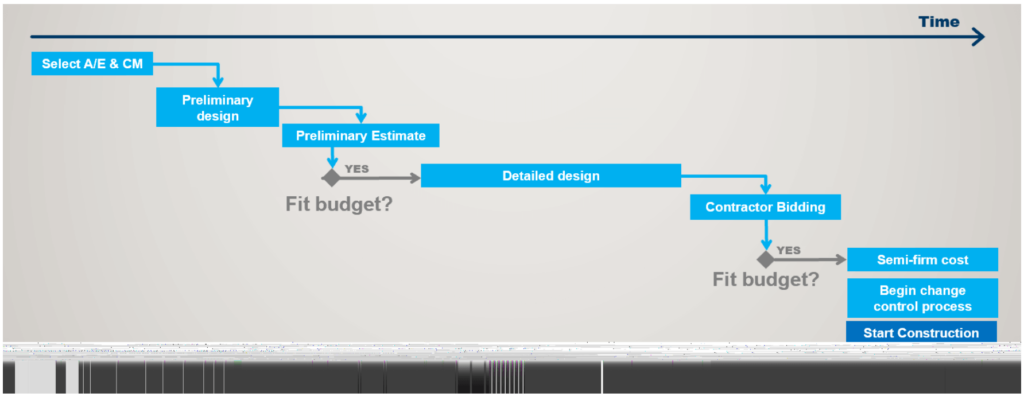

A simplified design and bidding process is illustrated in the sketch below, which shows a general sequence for many types of projects.

This general process is very well “tried” but not well “trued” due to some intrinsic problems, a few of which include:

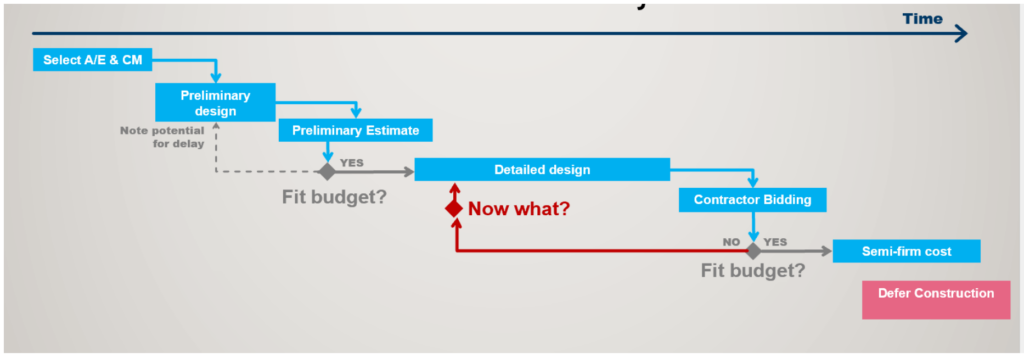

The intrinsic problems noted above are leading contibutors to the pervasive “now what?” situation shown in red below:

Finding out that project costs will exceed the Owner’s expecations after the design duration has been consumed and after the contactors have spent considerable time and effort to prepare bids and after the Owner’s project team has requested funding introduces all kinds of problems, which often include:

This pre-construction waste is built into the system to the degree that many of us fail to recognize it or simply accept it as inevitable. I’ve presented those diagrams countless times in many different forums. Participants universally report encountering the disruptive rework cycle “most of the time” or “nearly always”; the dysfunction is very real and highly pervasive.

Maximizing market leveage to secure the ‘best cost’ is the obvious driver of the conventional system but no allowance is made for the unintended costs and consequences. Efforts to recover the lost time involved as teams struggle to get the project underway were probably not incorporated into the original schedule or budget. Opportunity costs, including projects that might be viable but are unnecessarily scrapped, are not considered at all. Nor does the industry measure the time and money required to support the bidding (and rebidding) process from both the designers and the pool of contractors due an illusion the effort is free. There may be no invoices for estimating and bidding but those “free” estimates are costing somebody a bundle. That “somebody” is us as costs shift to the Owners and eventually to those that consume their products. [2]

There must be a better way to create projects. Let’s start by clearly stating that nothing in this text intends to discount the value or talents of design professionals. Quite the opposite: the CDS process frees up creative capability and allows those critical resources to focus on creative and collaborative options and solutions rather than a largely futile effort to create “tight” bidding documents. High levels of design effort and expertise are still required – but in a different form that allows for rapid iteration. Layouts, equipment lists, process flow diagrams, circulation diagrams and many other foundational design elements still need to be developed but they will be in a form tailored for evaluating options. We still need great engineers, designers and architects.

Shifting metaphors from waves to fires, I believe that frustration is to waste as smoke is to fire – find frustration and waste will be nearby – often in the form of lousy work processes. The rework and confrontation built into conventional project delivery is analogous to smoke from a forest fire– there is plenty of evidence of a sub-optimal process. The fuel for the fire will often be a fundamental misunderstanding of project scope, Owner expectations, risk and uncertainties. Unfortunately, efforts by the various participants to protect themselves through transactional behavior tend to feed the fire and create even more smoke. Lengthy, complicated and complicated contracts and commercial structures are hardly the best way to create alignment and work against the nature of the humans they are imposed upon.

Construction projects do not need to be so difficult and frustrating. With that in mind, let’s first explore a process to address the underlying lack of understanding and alignment at the source of the problems via a Collaborative Design and Scoping (CDS) process, a comprehensive method characterized by:

Imagine how much risk and contingency funding might be removed if contractors based their pricing on thoroughly understood scope they helped define – and are accountable for - rather than on bulky documents that cannot possibly be read within the time allowed for bidding. What if the contractors and designers jointly focused on delivering great results for the owner rather than posturing to protect their interests? Such arrangements would naturally improve both the project results and the experience. This explains much of the attraction of Integrated Project Delivery and Project Validation. It also explains my lack of interest in returning to the transactional delivery world.

Sometimes the CDS process reveals there is no workable solution set satisfying the Owner’s expected scope within their allowable cost. That’s not a failure of the process but rather an extremely valuable, yet sometimes underappreciated, benefit. The earlier we learn that a project is not viable the more waste we can avoid, and the earlier resources can be diverted to other projects.

The “Collaborative Design” aspects of the CDS process align with mainstream LCI thinking, including Target Value Delivery (TVD), Integrated Project Delivery (IPD), and Big Room thinking and will be familiar to many readers familiar with Lean Construction. The general ideas are well developed and described in many other papers so only this brief description is included in this paper. The “Scoping” part of CDS described below, however, is a critical part of the system that may not be familiar at all. Let’s explore how the work can be organized into useful, well-integrated chunks that can suit the needs of many different stakeholders.

Fundamental Scope Blocks (FSBs) are chunks of work or services that form the “building blocks” of the project for which Conditions of Satisfaction and Design Requirements can be defined and evaluated. Key characteristics include:

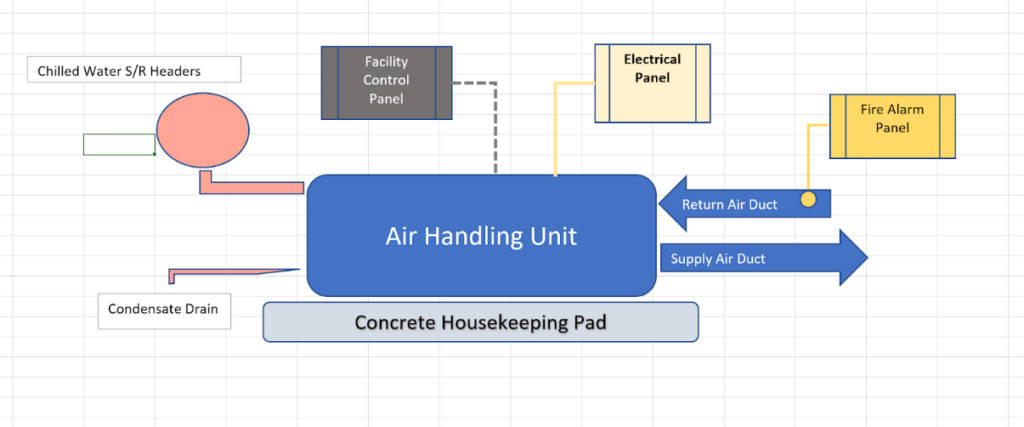

An air handling unit provides a great example of an FSB that appears on many projects and is illustrated on the simple graphic below.

The air handler provides a distinct utility to the project for which the design criteria and Conditions of Satisfaction can be concisely defined. It is easy for every design discipline, every contractor and the Owner to visualize what is required to make it function.

Imagine your last purchase of an automobile. You were likely very interested in the key features for which you had choices, such as audio system or the seating surfaces and how much the various options cost but you probably had no use for detailed quantity take-off detailing how many inches of wire or how many pounds of steel were involved. Typical construction estimates, even when the Owner gets to see them, do not organize the costs to enable key trade-offs between cost and features. Organizing costs by FSB is much more useful to the Owner and, if properly developed with Scope Activities, allows for the roll-up by system or discipline just like a more restrictive WBS.

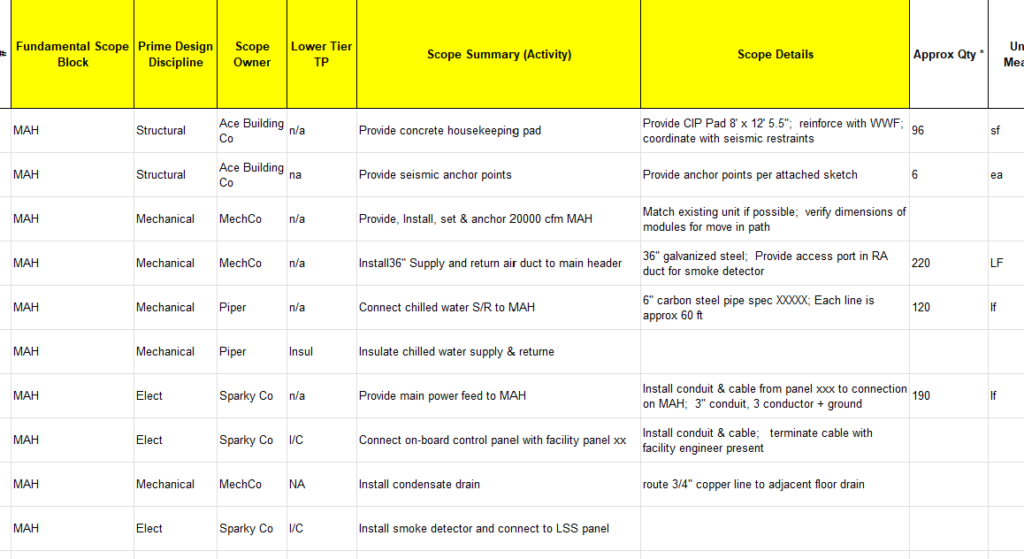

Scope Activities are the true heart of FSBs and an innovation I have been using since discovering them 25 years ago. Looking at the simple graphic of the Air Handling Unit it is clear to see that it sits on a concrete housekeeping pad, which will be designed by the structural engineer and installed by the concrete contractor. You can also see there will be chilled water supply and return lines from the chilled water headers that will be designed by the mechanical engineer and installed by the piping contractor. Similarly, there will be an electrical connection to an electrical panel designed by the electrical engineer and installed by the electrical contractor. These are examples of Scope Activities – the specific construction activities necessary to make the Air Handling Unit operational. Scope Activities have the following general characteristics:

Scope Activities are assigned to the FSB they serve. For example, the Electrical line feeding the Air Handling Unit shown above exists only to serve FSB. If the AHU were to be deleted that line would also be deleted. The electrical panel that supplies power, however, would still be needed and would therefore be part of a separate FSB, which might be labeled “Power Distribution Backbone”. This distinction is key for determining the number of FSBs needed. Scope Activities define not only the content of the FSB but also how the various FSBs are inter-connected. Understanding the Scope Activities is essential part of understanding the FSB.

A highly simplified list of Scope Activities for our hypothetical Air Handling Unit appears below to illustrate a useful level of detail.

Visualizing work that has not been designed is both a prerequisite for developing Scope Activities and one of the primary benefits. Experienced design and construction professionals typically enjoy the interaction when they develop the list together – which is key to successful use of the method. Estimators and design professionals discuss the Scope Activities to align on the key assumptions such that the estimator feels confident in the number they provide. The design team understands the factors that will affect cost and are much more likely to recognize potential cost changes during subsequent phases of design. Understanding the Scope baseline is the most important part of an effective change control process. A well-defined set of Scope Activities provides a foundation for that understanding. Site general conditions, temporary construction, project administration and any other element of Scope fit well within the FSB and Scope Activity framework rolling up to the total project cost and total contract values for each participant.

Understanding the Scope of each FSB during the CDS process takes far less time than allowing it to be slowly uncovered and challenged as the project evolves and the useful information is available far sooner. If projects move at the speed of Owner decisions (2), as I’ve heard many times at Lean Construction Institute (LCI) gatherings, then having solid information upon which to make their critical decisions represents one of the best, and least costly, ways to shorten the schedule.

Take a moment to think of a project for which there was a major cost overrun. Was the root cause an inaccurate quantity take-off or was there a failure to fully grasp the scope or requirements? You have probably already observed that Scope definition is much more important than detailed design when it comes to establishing a reliable project cost – and that Scope and design are not the same thing. Scope should be clear, concise and easy to update as new information emerges. That is in sharp contrast to an enormous set of comprehensive design deliverables that nobody will ever read as a unit – at least until it’s time to prepare or defend a claim.

The CDS estimating process requires a high degree of conceptual estimating skill – it requires people that can see what is not yet on the drawings. Quantity take-offs are not inconsequential and must be based on well-defined layouts and schematics, but exact dimensions are neither available nor required for conceptual pricing. This is one of the key insights underlying the FSB and Scope Activity approach. Estimators requiring comprehensive design documents in order to produce detailed quantity take-offs for unit price estimates are of little help.

A senior pre-construction manager told me than an estimate generated from the FSBs, Scope Activities and sketch level layouts was “within a +/- 15% range of accuracy” although based on “2% engineering”. His comment about “2% engineering” may have been a bit of hyperbole but make a key point: FSBs and Scope Activities help us address the Big Issues rapidly and reliably with far less chance of discarded design effort.

It seems clear that engaging trade partners early in the Scoping process improves communication, promotes innovation, and reduces risk but many projects are subject to contracting restrictions that prohibit this approach. That doesn’t mean you have to give up on the value of defining FSBs and Scope Activities. Visualizing and concisely describing key project features and requirements via FSB development allows the design and construction management teams to launch their efforts quickly with enhanced understanding of interdisciplinary coordination issues. This pays big dividends even if the trade contractors cannot participate in the early stages of the project. Organizing scope, cost, risks and uncertainties in the concise FSB format allows for rapid comprehension to reviewers and other intermittent participants and creates a very good platform for explaining the project to the eventual cast of characters. This partial approach to implementing the ideas of this paper will naturally provide only part of the benefits but may it best to start where we can and how we can.

The Construction Industry Institute (CII) and Lean Construction Institute (LCI) have formed a joint working group to explore how Lean thinking and AWP might be blended to create a new project delivery capability. The CDS process, FSBs, and Scope Activities could play a key role in bringing Lean thinking to projects committed to AWP with subtle, but critical, shifts in how the elements of AWP are organized. Likewise, AWP’s focus on identifying constraints will strengthen a critical, but often underdeveloped, aspect of Lean Construction.

The joint working group reached out to the Project Production Institute (PPI) to integrate that group’s expertise in Operations Science and creating flow. The ideas in this paper can improve the entire team’s understanding of the Scope of the projects and the nature of the chunks of Scope that will need to be managed by a project production system. A well-designed project production system will help us understand better how to structure and sequence those chunks of work into a system resembling smooth, laminar fluid flow instead of the highly chaotic and turbulent flow we see on too many projects today.

Remaining committed to doing things differently has surely had its costs, but the road less traveled was the right road for me. Hopefully you now have a few new insights regarding one of the industry’s most pervasive problems and ideas about a more natural, effective, and healthy way to work. Perhaps this paper reinforces what you have known all along – there must be a better way to deliver projects. There is much more to discuss. I look forward to the next round of comments and discussions.

Countless friends contributed to the ideas presented here. While listing all of them is not possible, some get special mention. Clients were the most important enablers. Special thanks go out to Steve Howard and Jeff Joyner from Hollingsworth & Vose and a host of friends from “confidential clients” in the micro-electronics, consumer products and pharmaceutical industries. The Neenan Company, including Hal Macomber, David Shigekane and Mike Daley were early like-minded collaborators that shaped my vision of collaborative design. Jeff Loeb, Terry Wheeler and Del Profitt were among many at CH2M that helped me implement the ideas on projects as were new collaborators at Burns & McDonnell. Harder mechanical’s pat Wenger showed me how to shift from unwieldy spreadsheets to a slick interactive database. And thanks to Dean Reed’s persistent nudge to get me to write this down.